History provides lessons for teams. Let’s take the time to explore a few of them.

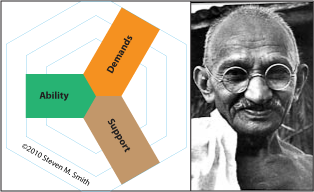

This post explores patterns that I see resulting from the interaction of ability, demands and support. Let me explicitly state what I mean by those variables —

Ability is the capacity to do something through talent and skill.

Demands are the problems that must be solved or managed.

Support is active help and encouragement.

The historical cases below are personified. We know these people as leaders, but they represent many people who worked with the leader to achieve some ends. Please note that the cases only refer to the point-in-time referenced.

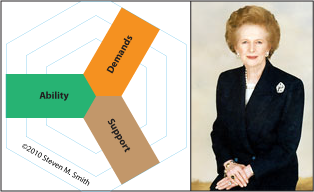

Margaret Thatcher skillfully led Britain as its Prime Minister from 1979-1990. She was more than able — she was a brilliant organizer, a first-class speaker and utterly focused.

When she became Prime Minister in 1979, the demands on her were formidable, such as nationalized industries that couldn’t compete with their global counterparts; a history of bitter labor strikes against nationalized industries; a burdensome and growing tax on the private parts of the economy; potential loss of supporters as she made changes; and the Cold War.

She privatized nationalized industries. She faced off against the powerful trade unions. She reformed the tax structure. She gained new supporters by selling public housing to its renters. She supported the reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

I think Thatcher’s personality comes shining through when she said, “Look at a day when you are supremely satisfied at the end. It’s not a day when you lounge around doing nothing; it’s when you’ve had everything to do, and you’ve done it.”

What lessons can teams learn from Margaret Thatcher experience as Prime Minister? Know your mission. Execute it skillfully. Constantly be looking for ways to gain new supporters.

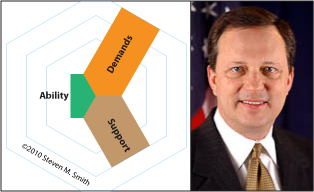

Michael D. Brown was Deputy Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) who was swamped during the Hurricane Katrina disaster of 2005. Brown appears to have had virtually zero background in emergency management prior to his appointment as Deputy Director of FEMA in 2003. The bulk of his career having been spent practicing law and as Commissioner for the International Arabian Horse Association.

Up until Hurricane Katrina, FEMA had been considered a model federal agency because of its successful responses to past disasters, such as the Midwestern floods of 1993, the Northridge earthquake of 1994, and the Oklahoma City terrorist attacks of 1995. When the demands from Katrina became known, FEMA’s response was considered by many, especially by the residents who were caught in the path of its destruction, as an utter failure.

Email messages sent by Brown during the disaster tell something about his ability. He wrote, “Can I quit now? Can I go home;” and “trapped (as FEMA head) … please rescue me.” I can’t imagine any circumstances in which Margaret Thatcher would have ever sent similar messages. Less than 45 days after he had sent the email message, swamped and resigned, Brown quit his Deputy Director position.

Did Brown have all the support necessary to respond satisfactory to the demands caused by Hurricane Katrina? No, I don’t think he did. The organization of federal emergency agencies had change considerably after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Regardless, I think his poor ability eroded support he could have had and prevented him from maximizing the support he did have.

What lessons can teams learn from Michael Brown’s Hurricane Katrina experience? Know your ability. If your demands outstrip your ability, find more support or find a different mission.

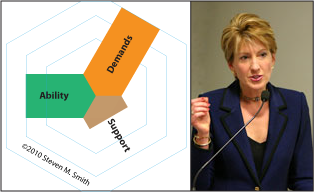

Carleton (Carly) Fiorina was CEO of Hewlett-Packard (HP) from 1999-2005. Her command ship was scuttled in 2005 when she lost the support of HP’s board.

Prior to HP, Fiorina was the executive vice president at AT&T responsible for spin off and initial public offering of Lucent Technologies. She joined Lucent’s executive management team where she was chairman of a joint venture and later a group president for its global service provider business. I think it’s fair to say she was a person of proven ability.

When she became CEO of HP, the demands on the business were considerable. It had been unsuccessful at exploiting the Internet. It had lost ground to perennial rivals IBM and Sun Microsystems. And Compaq and Dell Systems were growing thus eroding HP’s share of the PC market.

In 2001, Fiorina’s plan was to break up HP and merge the parts she kept with PC maker Compaq. HP board member Walter Hewlett (the son of the “H” in HP) publicly objected to the merger describing it as an act of desperation. David Packard (son of the “P” in HP) publicly said that the merger plans were a cruel departure from the values and corporate culture of HP’s founders.

Describing the situation, Fiorina said, “Most of the media… is positioning the merger with Compaq and the recent actions by Walter Hewlett and David Packard as a fight between the past and the future.”

Fiorina won the battle for the future, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. The win had cost her support. She continued to win battles, but lose supporters. Each lost supporter drilled another hole in the hull of her command ship. Eventually the bilge pumps couldn’t keep up and the ship sank.

What lessons can teams learn from Carly Fiorina’s HP experience? Support is precious. Find strategies that supporters believe are right even if they aren’t your favorites. Constant fighting with supporters, especially public brawls, will eventually scuttle your ship.

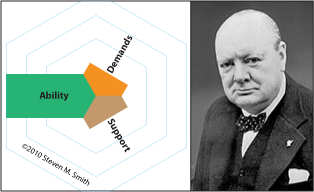

After successfully leading Britain through World War II, Winston Churchill’s Conservative Party lost the election and he was forced to step down as Prime Minister. It crushed him. Without popular support and the high-demands of being Prime Minister, he grew frustrated and bored.

Never a ray of sunshine, his sarcasm and black moods increased. Although he remained in Parliament, he brooded over the atomic bomb, the Soviet menace, and creating “a United States of Europe.” But he had enormous amounts of free time compared to the war years as Prime Minister.

He channeled his unused ability into writing and painting. He was excellent at both. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature and his impressionist paintings have been exhibited around the world and continue to attract attention. On painting, he said, “Armed with a paint-box, one cannot be bored, one cannot be left at a loose end, one cannot ‘have several days on one’s hands.'”

But things change. Uncertainty about foreign threats created demands that matched his ability. Support began building. In 1951, his Conservative Party won a majority and Churchill returned to being Prime Minister.

What lessons can teams learn from Winston Churchill’s post-World War II experiences? Don’t waste your talent and skill. Focus your unused ability on activities that provide you with a sense of accomplishment. Keep supporters aware of your abilities. Things will change.

Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi energized and led the Indian subcontinent out of British domination. I consider him the greatest change agent of the Twentieth Century.

After ten years of leading the civil rights movement in South Africa. Gandhi returned to India in 1915, He faced daunting demands. British dominance had become the status quo for two generations of people born on the Indian subcontinent. And Britain was determined to maintain the dominance by all means necessary.

Using methods of nonviolent resistance, a philosophy of fearlessness, and his personal example, his Indian independence movement gained more supporters. And with more support came new demands, which called for him as leader to develop new skills. One generation after his return, the movement won its independence.

I question whether anyone would have said in 1915 that Gandhi had the ability to successfully lead a movement of this size and complexity. But I believe he convinced himself that he could and in the process energizing himself and his followers to develop the necessary skills.

Gandhi said the following about acquiring ability, “Men often become what they believe themselves to be. If I believe I cannot do something, it makes me incapable of doing it. But when I believe I can, then I acquire the ability to do it even if I didn’t have it in the beginning.”

What lessons can teams learn from Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle for Indian independece? Have faith. Believe in yourself. Set an example. Use the difference between your perceived skills and your desired skills as energy for bridging that gap.

§

What’s the difference between the cases of Thatcher and Gandhi versus Brown, Fiorini and Churchill? Support. If your team is failing to nurture support, you will fall.

What’s the difference between the cases of Thatcher and Gandhi? Thatcher had an existing (governmental) structure to use to implement her policies. Gandhi had to create a new structure. Thatcher was clearly skillful and energized, but Gandhi’s movement seems to me to have required much more energy.

Did Brown fail because he didn’t believe in himself like Gandhi did? No, I suspect Brown did believe in himself. He may, however, have suffered from hubris. With better support, he may have been able overcome demands that swamped him. But he apparently didn’t foster that support.

What does the case of Churchill tell us? An active life is bound to have set backs. The period described wasn’t Churchill’s first set back. With support, our abilities can be applied to larger demands.

What would you add to this analysis?

Having read this I believed it was extremely informative.

I appreciate you spending some time and energy to put this article together.

I once again find myself spending way too much time both reading and

commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!